Huichol shamanism: traditional wisdom in a modern world

Chamanismo huichol: sabiduría tradicional en un mundo moderno

This article explores the ancient tradition of shamanism and its many facets in Huichol Indian culture. The Huichol Indians (Wixárika, Wixáritari pl.) live predominately in the Mexican states of Jalisco and Nayarit in their remote mountain homelands of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Their shamans have been vital keepers of ancient esoteric knowledge and leaders, healers, and diviners for their people. The shamanic tradition is passed down primarily through family kin ties. The path to becoming a shaman and the plants and animals that are shamanic allies will be discussed. This is followed by an examination of the shaman’s power objects and the wide array of specialties acquired. Finally, the article addresses the challenges to shamans in the 21st century and their crucial role to the survival of Huichol culture and identity.

Keywords: shaman, Huichol, Wixárika, peyote, tobacco, solandra, Mexico.

INTRODUCTION

The Huichol indians of Mexico, also known as the Wixárika (Wixáritari pl.), a name they use to refer to themselves, are renowned for the number of practicing shamans present in their communities and the breadth of their expertise.(1) In the 1890s the Norwegian anthropologist, Carl Lumholtz, visited Huichol Indian communities in the Sierra Made Occidental predominately in the states of Jalisco and Nayarit.(2) In his account, Lumholtz discusses the etymology of their tribal name which he spells as “Vira’rika”. He writes:

According to some Indians, the name means ‘prophets’ (Sp. adivino). According to others, it means ‘healers,’ ‘doctors’, (Sp. curandero). This latter would be very appropriate, as every third person seems to be a doctor, and the fame of the Huichol healers extends far beyond their own country. Many of them make annual tours, practising their profession among the neighboring tribes […] (Lumholtz 1900: 5-6).

The Huichol people have been called “A Nation of Shamans” because of the number of shamans and the prominent role they have had since pre-Contact times and continue to have in their communities today.(3) Shamans are known as mara’akame (mara’akate pl.) in the Huichol language and follow in the footsteps of their kin elders and ancestors. They are the intermediaries between the supernatural world, the world of the ancestors, and the world of the living. Their dreams and visions from the entheogenic peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii) empower them to travel through these worlds to communicate with the gods for direction and actions to be taken in daily and ceremonial life. Huichol shamans are vital leaders, healers, and diviners who through their practice remain keepers of ancient Huichol cultural knowledge (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Petroglyph on the path to the community of San Andrés Cohamiata. Huichols say that it was made by the hewi, the ancient ones (all photos by the author, with the exception of figure 9). Figura 1. Petroglifo en el sendero a la comunidad de San Andrés Cohamiata. Los huicholes dicen que fue hecho por los hewi, los antiguos (todas las fotografías son de la autora, excepto la figura 9).

The information presented in this article draws from the author’s ethnographic research which spans over four decades among Huichols predominately from the community of San Andrés Cohamiata. The methodology employed consists of participant observation (the author’s five-year path to become a master weaver that closely parallels the path to becoming a shaman); participating in ceremonies and pilgrimages including four trips to the peyote desert, Wirikuta, in the state of San Luis Potosi with Huichols led by a shaman; as well as interviews with shaman consultants. This on-going long-term research seeks to understand Huichol shamanism from the perspective of Huichol shamans, through the author’s experiences, and from the work of other scholars of Huichol Indian culture. The training to become a shaman and the plants and animals with which shamans form alliances will be outlined to provide a general understanding of the unique ways shamans learn their craft in Huichol culture. The power objects germane to practicing shamans and the metaphysical powers ascribed to these objects will be discussed as well as the wide array of specialties acquired by shamans. This paper will address the challenges to shamans and this ancient shamanic tradition along with how the shaman with his/her ancient esoteric knowledge remains relevant and crucial to the survival of Huichol culture and identity in the 21st century.

THE PATH TO BECOMING A SHAMAN

Shamans may begin their apprenticeship as children or at any stage of adult life. Their training usually takes place within the context of the family ranch.(4) Huichol spiritual specialists can be male or female; however, male shamans dominate the public sphere. Female shamans are wary of having such a prominence as they fear accusations of practicing sorcery on others, and consequently many female shamans prefer to attend to extended family in their ranch environments (Schaefer 2015). Regardless of gender, apprenticing to become a shaman follows the same path. For some, the calling to become a shaman begins early in life, and the indications for this are varied. A child may show an interest in playing the ceremonial drum, have the ability to dream about the gods, or have a proclivity to smoking the sacred tobacco (Nicotiana rustica) which contains high levels of nicotine and is used by shamans for ceremonial purposes. A child may be drawn to consuming peyote; in fact, children whose mothers consumed peyote while they were in utero are considered more likely to become shamans (Schaefer 2011, 2017). A young one who recovers from a life-threatening illness is viewed as having traveled to the other side but has returned to the world of the living; this is also a sign that the gods have determined this child should become a shaman. These instances and others are divined by the family shaman or elder of the extended family and interpreted as a sign that the child is destined to be a son or daughter of a particular god such as: the fire god, Tatewari; the god of the deer, Paritsika; the god of rain, Nü’ariwame; the god of fertility and childbirth, Niwetükame; etc. If an individual has not experienced any profound event early in life, he or she can still pursue this specialized training; however, it will be more challenging, and the person will have to work extra diligently to achieve such a powerful role. This also means it could take more years to complete the apprenticeship, and some never succeed in this quest.

An important requirement throughout the training is that the shaman initiate must remain chaste or faithful to a spouse for the five or more years on this path. The key is to focus one’s energies, thoughts, and actions towards this goal. Distractions that cause one to deviate from the training can cause illness and hardships as punishment. The seriousness of staying the course means no one may marry during the five or more years of training. As such, it is more likely for an individual to begin this endeavor once married. Huichols tend to marry at a young age, usually during adolescence. Huichol culture allows men to have polygynous marriages, but a shaman apprentice must not take an additional wife until he completes his training. This also implies that the husband of a female shaman initiate must not marry another woman while his wife is completing her apprenticeship.

To begin the training, the novice seeks another shaman to guide him or her through the process. Again, this responsibility usually lies with the family shaman in the ranch or another shaman kin member who will dream to which gods the apprentice needs to form special alliances by making vows and leaving offerings to them in their sacred places. In essence, Huichol shamanic traditions follow along bilateral kin lines from generation to generation since the knowledge imparted comes from shamans who are members of the same kin groups, and each kin group has its own specific ways of practicing shamanism that is literally informed by ancestors. The shaman mentoring this work will also interpret the novice’s experiences, dreams, and visions as signs sent from the gods and advise him or her in the subsequent actions to be taken.

The most common offerings consist of votive bowls and arrows. Hard-shelled gourds are dried, cut in half, scraped clean, and used as offering bowls. Inside of each bowl the petitioner makes miniature figures from beeswax that are affixed to the inside wall. These figures are usually simple figures representing the person offering the prayer and his or her family, a deer, a corn plant, and a circular coiled mandala design in the center. This latter design is called nierika, and is seen as a portal, a doorway that sends the person’s prayers to the world of the gods. Beads in various colors are carefully pressed into the wax (Kindl 2003). Votive arrows are made from brazilwood and hollowed cane that are decorated with paint made from seeds, minerals, and oil to create the colors black or red. A candle, preferably of beeswax, also accompanies the set of offerings for each god to which the novice has made a vow for guidance. These offerings are brought alive by anointing them with the blood of a sacrificial animal before they are left for the gods to hear the petitioned prayers (Gutiérrez 2000) (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Ceremony in which a year-old calf is sacrificed. Its blood is collected to anoint offerings for the gods. Figura 2. Ceremonia en la que un becerro de un año de edad es sacrificado. Su sangre es recolectada para ungir las ofrendas a los dioses.

During the five or more years to complete this training there are two crucial achievements the apprentice must master. One is to be able to remove illness-causing objects from a patient’s body, which are most likely to physically manifest as kernels of corn (maize), small pieces of charcoal, small stones, or deer hair. One shaman (personal communication), explained the learning process this way:

At the beginning of the rainy season [around end of June] the person fasts and selects corn seeds to plant in the center of the milpa [cornfield]. He/she brings sacred water from faraway places, leaves prayer arrows there and has to pray [to the gods] for power [to be able to heal, by means of removing illness causing objects in the body] to become a shaman. When the corn begins to sprout within five days one has to present a votive bowl and prayer arrow. Then some go deer hunting […] if it is not deer-hunting season then one may go to the river and catch a fish for its “blood” to anoint the offerings and feed the hole in the center of the milpa which represents the mouth of the moist earth goddess, Yurianaka (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Offerings of votive bowls, prayer arrows, candles and peyote are left by the hole in the center of the cornfield for the moist earth goddess, Yurianaka. Figura 3. Ofrendas de cuencos votivos, flechas de oración, velas y peyote son dejadas cerca del agujero, en el centro del campo de maíz, para la diosa de la tierra húmeda, Yurianaka.

Rafael’s cousin María Paulita Minjares, who is also a shaman, relates that if one seeks shamanic power through making vows in the milpa the apprentice fasts for five days until the corn plants first sprout, at which time he or she must eat five little corn seedlings in order to gain esoteric knowledge.

The second step is when one is going to clean the weeds in the milpa:

You sacrifice something there ‒a chicken, a sheep. The third step, when the ears of corn are just beginning to form, you kill a deer on the deer hunt as a sacrifice. The fourth step, when the ears of corn begin to emerge and are young and tender, you sacrifice a deer and a cow. The fifth step is when the ears of corn have completely emerged. You wash your hands with sacred water to purify and bless everything there, [including] votive bowls, arrows, and candles (Rafael Pisano, personal communication).

The animals that will be sacrificed include the ones mentioned above. The sixth step is when the corn is harvested and brought home which commences the harvest ceremony –Tatei Neixa (Dance of Our Mothers) and sacrificial animals are sought to anoint offerings with their blood and provide food for the participants.

Rafael continues that in order to heal through sucking out illness-causing foreign objects from a patient’s body such as kernels of corn that the shaman in training must encounter and communicate with the Deer Person, Kauyumarie, who is the messenger god for shamans:

One has to do these five steps every year. The first year one does not know much if anything. The second year one knows a little more, some by the third year [are able], others the fourth year, fifth year, sixth. Some do not learn at all […]. If you reach five years and you do everything correctly but haven’t learned, and if there is not a shaman by your side to help you, then you will encounter this animal. It will appear as an animal […] you may find it in the center of the milpa, you may encounter this animal as a deer. Sometimes you find people in the center of the milpa. If you find a deer, you grab it. As a result, in your hand you will discover something, a small gourd bowl, the horn of an animal, sometimes a rock crystal (Rafael Pisano, personal communication).

He says that the tutelary god, Kayumarie, may appear in various ways:

When you reach the fifth year you will dream all that you encountered, and you present it in one of various possible sacred places. That’s how you will be lucky and the gods will explain things to you in your dream. When you go to these places you will not find a person. It’s more like the wind, a breeze, a whirlwind, and everything becomes very clear. It is Kauyumarie. If you are successful on your path then you will encounter a person, a god, and you grab it. You may find [in your hand] a candle, a feather for your shaman’s power wand [muwieri], it will be something that will remain with you (Rafael Pisano, personal communication).

While explaining this, Rafael takes various power objects that he acquired over time in this way out of his shaman’s basket, takwatsi. One small rock, he said, he grabbed from within the peyote and declared it was Kauyumarie. Another rock he grabbed when he was in the milpa ritually dancing. A third rock he said he found in his bowl of meat stew made from an animal ceremonially sacrificed. Rafael takes out another small rock that he says is Tamatzi, Elder Brother Deer, and it is good for when you have been having a difficult time finding deer during the hunt. He says that you sing and eventually will find deer (fig. 4).

Figure 4. The shaman, Rafael Pisano, with feathers in hat that are used for ceremonial objects and shaman power wands. Figura 4. El chamán Rafael Pisano con sombrero con plumas, las que son usadas para los objetos ceremoniales y las varas de poder chamánico.

The second crucial achievement is for Kauyumarie to manifest himself to the shaman apprentice and teach the novice to sing. For the beginning initiate, Kauyumarie may appear as a human. The first time he made himself known to the shaman María Paulita Minjares, he appeared as a child. She explained to me via her son, Rafa Hernández, that

she saw a child that came to talk to her in her dream. Like all shamans, the child smoke tobacco [makutsi, N. rustica] because it helps shamans dream and they are never without. This child that Maria Paulita saw was bald. They say that the fire god, Tatewari, is also this way. She talked with this child who appeared to be a young boy, but he was a man because he was smoking this tobacco (Maria Paulita Minjares, personal communication).

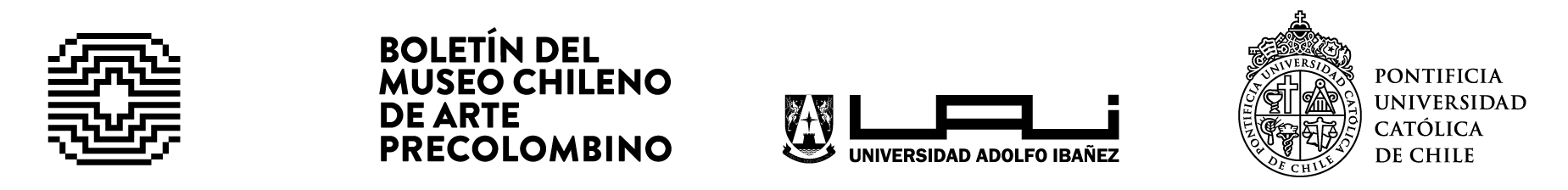

Once Kauyumarie’s presence is familiar to the seeker, from then onward he will appear as a deer person. He converses with the shaman and he relays the responses from the gods to particular inquiries the shaman may pose (fig. 5).

Figure 5. The shaman, María Paulita Minjares, prays with the peyote in Wirikuta as she holds her muwieri, feathered shaman wand, and a beeswax candle. Note on her woven bag for carrying offerings the deer with peyote designs on its body representing the shaman’s messenger god, Kauyumarie. Figura 5. La chamana, María Paulita Minjares, reza con el peyote en Wirikuta mientras sostiene su muwieri (la vara chamánica emplumada) y una vela de cera de abeja. Nótese en su bolsa tejida para portar ofrendas, el venado con diseños de peyote sobre su cuerpo, representando al dios mensajero de los chamanes, Kauyumarie.

An essential milestone required to become a shaman is to be taught by Kauyumarie to sing. Rafa Hernández (personal communication) described his experience, noting that in this first encounter with Kauyumarie he appeared as a woman:

I dreamed of a person that I know who is not from San Andrés Cohamiata […]. She gave me feathers, one was a royal eagle’s feather [to be used as a muwieri, shaman’s feathered wand], and the feather included two candles.

We sat down.

“We are going to sing” she told me. “I’m going to sing first, then you follow.” I told her that I couldn’t. I doubted I could sing.

She told me “you sit here”.

She sang a round of the song and Rafa Hernández followed by repeating her song. Rafael (personal communication) continues that afterwards:

She gave me a copa of tequila.

“Here” she said, “you are succeeding in becoming a shaman, you are earning your life, nothing more. You are not earning money. This is the only thing we are earning. It’s because you helped me. Drink up” she told me… “Where do you live?” I asked her.

“I’ll tell you” she said, “but don’t tell anyone else.”

She pointed to a hill filled with many nopal cacti and huitzache shrubs.

“I live over there between the nopal fields. My house is there. The day you come looking for me you will find me there. I will wait for you. But don’t tell anyone”.

ANIMAL ALLIES

Those training to become shamans will inevitably strive to make alliances with animals and plants that are deemed to have unique powers. Certain reptiles in their homelands such as the horned toad (Phrynosoma), Mexican beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum), and boa constrictor (Boa constrictor) are sought on this quest. When provoked, the horned toad squirts blood from the corners of its eyes to a distance of up to 1.5 m (Middendorf et al. 2001). Since blood is important in offerings to the gods, shaman apprentices may make a pact with the horned toad (teka) requiring that over the five-year training period they catch five horned toads, induce them to bleed, and with this blood anoint their cheeks, inner wrists, and the tops of their feet. Upon thanking the horned toad, it is released.

The Mexican beaded lizard (‘imukwi) bites its prey, injecting venom through salivary glands in its lower jaw (Beck 2005). Forming an alliance with this reptile requires that the shaman in training catch a total of five over the course of the apprenticeship, carefully cut a small piece of the tail to cause it to bleed and anoint oneself as described above. Each beaded lizard is thanked and released into the wild. Forming an alliance with the boa constrictor (wiexu) follows the same procedures. This snake is an ambush predator; it is not venomous to humans but does bite. It kills by striking and constricting its body around its prey, likely shutting off blood to its heart and brain (Gill 2015).

The hearts of some freshly-hunted animals are eaten raw as it is believed that doing so imparts the special qualities of the animal and, hence, its life-essence into the body of the shaman apprentice. Hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are admired by Huichols for their speed and agility. The shaman in training catches up to five hummingbirds and eats the hearts. Some novices are also instructed to eat the heart of a recently-killed deer so that he or she can become one with this sacred animal that is fundamental to their cosmology.

PLANT ALLIES

Plants with which shaman-apprentices may desire to form a special relationship invariably have psychoactive properties. Shamans may know of plants for herbal remedies, but they believe the power to heal lies in plants that imbue them with visionary experiences and metaphysical powers.

Tobacco

The special, potent tobacco used by Huichol shamans, makutsi (N. rustica), is most likely the oldest of the nicotine-producing tobaccos cultivated by Indigenous peoples in the Americas in pre-Contact times (Wilbert 1987: 6). The nicotine content in the leaves of this tobacco is as high as 18.76% (+/- 2.6%) compared to N. tabacum used for commercial cigarettes with a lower nicotine level ranging from 0.6 to 9.0% (Siegel et al. 1977: 22; Wilbert 1987: 134). This tobacco can induce an altered state of consciousness. The consumption of high concentrations of nicotine must be done judiciously, otherwise death can occur from nicotine poisoning. Shamans are the primary growers of makutsi, the sacred plant of the fire god Tatewari, and the knowledge of how to use it and carefully cultivate it is passed on from shaman to the initiate. Leaves of this tobacco are carried by shamans in hollowed-out gourds that are strung across the shoulder and smoked in rolled corn husk cigarettes or clay pipes (fig. 6).

Figure 6. Huichols participating in the ceremony Hikuri Neixa, Dance of the Peyote. The pilgrims, who had returned from the peyote desert of Wirikuta, wear turkey feathers in their hats, symbolic of the myth in which the turkey named the sun when it first rose. Note the small gourds that contain makuti, the sacred tobacco of shamans, carried across the shoulder of the man on the left. Figura 6. Huicholes participando en la ceremonia Hikuri Neixa, Danza del Peyote. Los peregrinos que han regresado del desierto del peyote de Wirikuta, portan plumas de pavo en sus sombreros, símbolos del mito en el que el pavo nombró al sol cuando este se alzó por primera vez. Nótese las pequeñas calabazas que contienen makuti, el tabaco sagrado de los chamanes, colgando del hombro del hombre a la izquierda.

Peyote

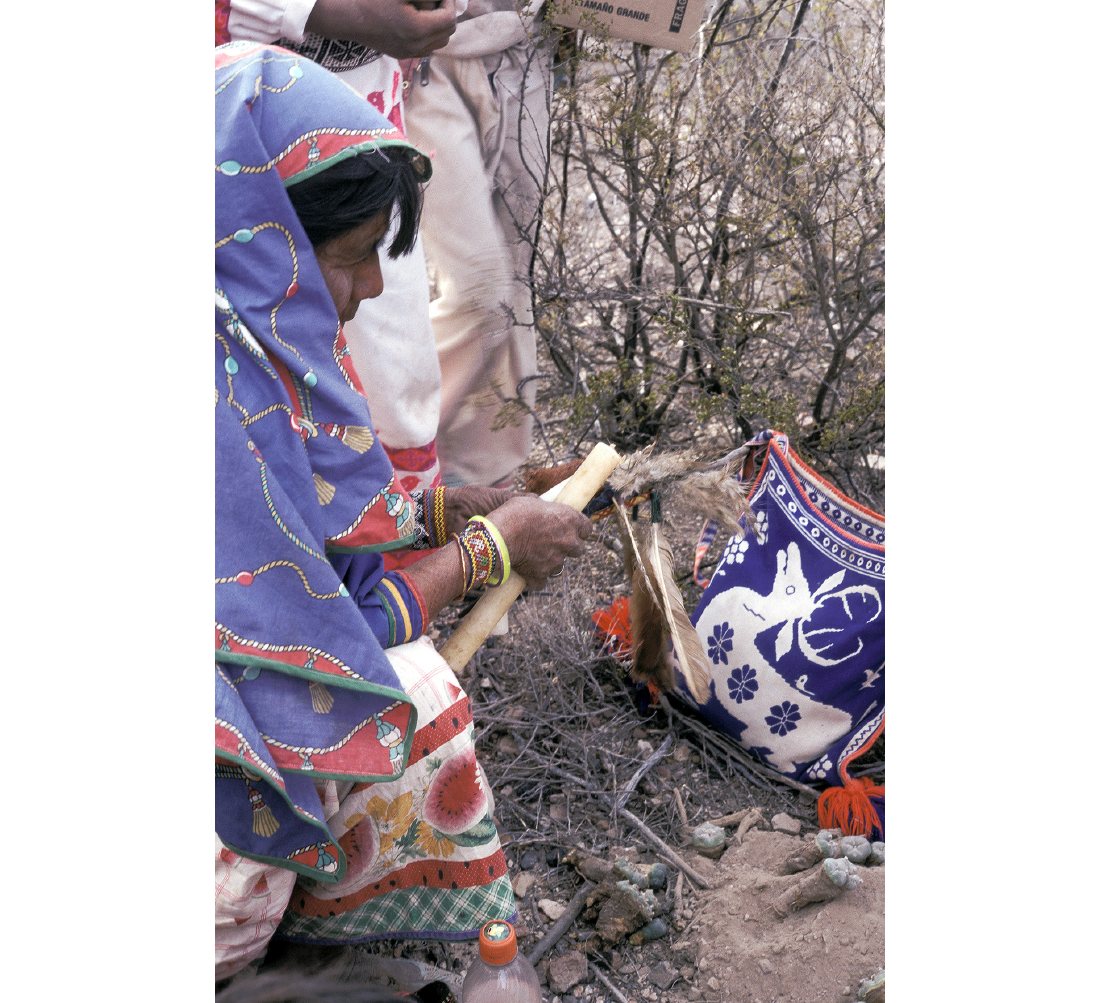

Peyote is revered as a powerful plant ally. Forming a relationship with this vision-producing cactus enables shaman apprentices to travel deep into the Huichol cosmos to learn life-transforming lessons and gain greater access to the gods and to other worlds (fig. 7a).(5) Peyote is a spineless, low-growing cactus that contains over 60 alkaloids; the most abundant alkaloid is mescaline (3, 4, 5- trimethoxyphenethylamine) which is credited with inducing mind-altering experiences. It is not unusual for parents to introduce their children to peyote within a familial ceremonial context (fig. 7b). Peyote is especially sought by those on the shamanic path. An initiate may focus on learning to become a shaman in the peyote desert, known as Wirikuta, in the Mexican state of San Luís Potosí. There, under the watchful gaze of Wiri’uwi, the peyote goddess, a shaman apprentice may go to commune with this visionary plant and seek to meet up with Kauyumarie. One shaman, Guadalupe Carrillo (personal communication), describes a stunningly vivid experience he had eating peyote in Wirikuta at a young age as related below in abbreviated form:

I made some votive arrows for Kauyumarie, the deer god, to leave where there is peyote in Wirikuta. They were for Kauyumarie because he knows everything; he knows everything about the world […]. When I arrived in Wirikuta I left one of the arrows […] the other peyoteros [pilgrims] took out a large gourd bowl and filled it with peyote. They told me that since this was my first trip to Wirikuta I had to eat all of the peyote in the bowl. I wanted to know about god, how the world began, how the sun first appeared, how the fire, the maize, the earth and the god of rain first appeared […]. I continued eating [peyote]. Then I finished.

One of the votive bowls [on the ground] was decorated inside with beads in the figure of a deer. In two or three hours I looked at the votive bowl and the deer inside the bowls was really large. How can that be? I continued eating more [peyote], and as I was looking into the votive bowl the deer grew in size and jumped out of the bowl. It was standing on the ground and moved in front of us.

Then I found a large peyote, I was looking at it and there was a little deer on top of the peyote where the white tufts of the plant are. It was a tiny little deer – how can that be? I’m seeing deer everywhere, why? I remember hearing my grandfather […] say that this is the way that you always begin to learn. And with the peyote it is the same.

Well, the peyote was really, really large […] the deer passed very close by me. I was in the middle of the peyote where the white tufts are. I [must have] flown up there, I was seated in the middle of peyote and I flew higher up, to the mountain top of Cerro Quemado [an inactive volcano above Wirikuta where offerings are left]. I was standing up there and I was looking at the whole world –the ocean looked really small. I not only saw the ocean but all the animals that live in the ocean, whales, snakes, mermaids… everything. [The deer told me] […] you should be calm… then I was back down below in Wirikuta […].

Figure 7: a) peyote (L. williamsii), a mind-altering spineless cactus that is sacred in Huichol culture and a major plant ally of shamans; b) Huichol families gathered at their aboriginal temple for the ceremony Hikuri Neixa, Dance of the Peyote. Over the various days of the ceremony, participants will consume a drink of dried peyote ground and mixed with water and fresh peyote that has been harvested in Wirikuta. Figura 7: a) peyote (L. williamsii), es un cactus sin espinas alterador de la consciencia, sagrado en la cultura huichol y una de las principales plantas aliadas de los chamanes; b) familias huicholes reunidas en su templo indígena para la ceremonia Hikuri Neixa, Danza del Peyote. Durante los varios días que dura la ceremonia, los participantes consumirán una bebida hecha de peyote seco molido, mezclado con agua, y peyote fresco que ha sido recolectado en Wirikuta.

Admixture plants

Eventually, if one succeeds in completing the shamanic training, he or she will also acquire an expertise in the mixing of plants to modify or enhance the effects of peyote. The use of the tobacco, makutsi, in conjunction with consuming peyote brings greater control to the peyote experience when specific tasks are required or clear thinking desired. Rafael Pisano (personal communication) explained this to me:

You pray […] that you will get something from it (the peyote) that you will gain more knowledge, see things, not get nauseous or vomit […] and then when you smoke makutsi you will not feel so empeyotado. Even if you eat lots of peyote, you will not feel it that much […] it makes one feel it gently, that’s how people do it […]. Because if you eat peyote you feel differently, sometimes [the peyote] is gentle, sometimes it is very heavy […] and then you hear things from far away, people talking from far over there. But with makutsi no, it lessens the feeling of being drunk with the peyote […] so that you come down, that’s why they smoke […] you get the urge to smoke when you eat peyote.

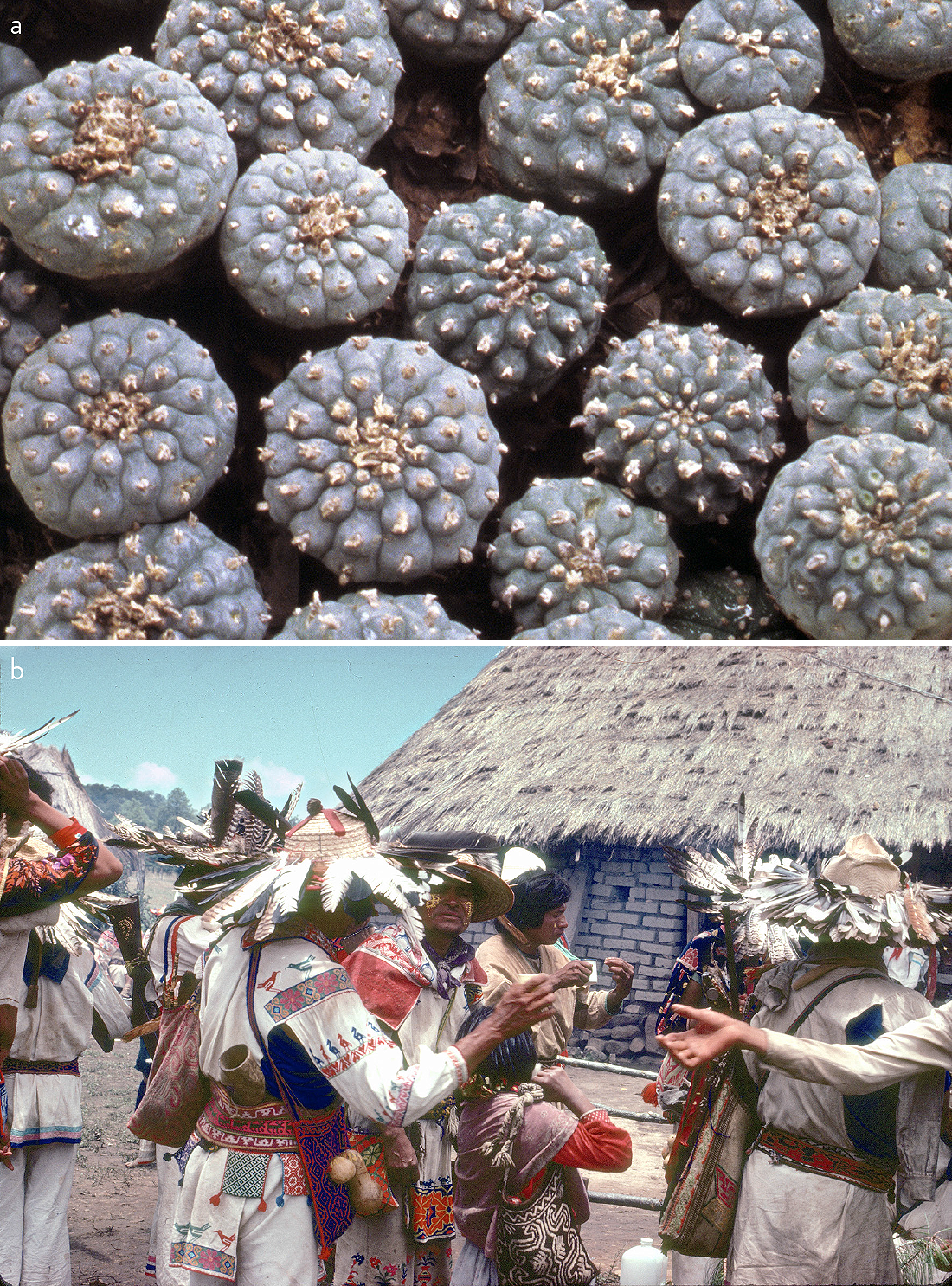

Other plants that are sometimes ingested along with peyote include slices of a barrel cactus they call maxa kwaxi. Under the direction of a shaman, a section of this cactus is cut, the spines are removed, and it is cut into slices. When it is eaten in combination with peyote, it lessens the effects of peyote. Slices of another cactus (Ariocarpus retusus) and the root of another plant they call ‘uxa (Mahonia trifoliolata) that grow in Wirikuta are also admixture plants consumed with peyote. ‘Uxa is ground and mixed with water to make yellow paint to adorn the faces and ritual objects of the peyote pilgrims (fig. 8a and b). Rafael Pisano (personal communication) describes his experience combining ‘uxa with peyote:

[The ‘uxa] this you feel with the peyote. You feel more, but it is different, it is not like smoking makutsi […] it does not lower the strength like with makutsi […] when you combine [‘uxa and peyote] it is as if they elevate you, they raise you up zzzzzooooommmmm. That’s how I felt. I saw the whole world very small, very round. I was moving as if I were the sun, that’s the way I saw everything. I saw the gods, where they come from and where they reside. I saw everything. That’s what happened to me when I ate ‘uxa [with peyote].

Figure 8: a) a piece of the root of ‘uxa (Mahonia trifoliolata) is ground and mixed with water to make paint; it is also used as an admixture with peyote. Huichols who are peyote pilgrims paint their faces and sacred objects, such as the cow horn which is sounded by hunters on the deer hunt to communicate between themselves without alerting the deer of their presence; b) a young girl with face paint from the ‘uxa root (M. trifoliolata) who has gone on the peyote pilgrimage with her family. Figura 8: a) un trozo de la raíz de ‘uxa (Mahonia trifoliolata) es molida y mezclada con agua para hacer pintura; también es usada como aditivo al peyote. Los huicholes que son peregrinos del peyote pintan sus rostros y objetos sagrados, como el cuerno de vaca que es tocado por los cazadores en la caza del venado para comunicarse entre sí sin alertar al animal de su presencia; b) muchacha que ha ido al peregrinaje del peyote con su familia, con pintura facial de la raíz ‘uxa (M. trifoliolata).

Solandra

There is one powerful plant in the shamanic pharmacopeia that is feared by many and sought by those that have the greatest determination to gain power from it. This flowering plant they call kieri is a Solandra that is laden with the alkaloid scopalamine that induces a very different experience (fig. 9). Kieri grows among rocky, craggy cliff sites and with its fragrant flowers it beckons only the most courageous seekers to visit and commune with it. Shamans, as well as others who wish to learn from kieri, make a pilgrimage to visit the plant, leave offerings to it, and cut a small piece from the plant to consume. Some spend the night under this alluring fragrant plant in hopes that their dreams will reveal important messages to them.

Figure 9. Flower of kieri (Solandra), a plant that is both feared and sought for acquiring special powers by some shamans (photo by James A. Bauml). Figura 9. Flor del kieri (Solandra), una planta que es temida y al mismo tiempo buscada por algunos chamanes para adquirir poderes especiales (fotografía de James A. Bauml).

Kieri is considered to be so powerful that others may not ingest it at all, but will keep a piece of it in their shaman’s basket, or their bag of offerings, to ask for luck in their petitions whether it be advancing shamanic aspirations, perfecting the ability to play the violin, or artistic desires to excel in weaving and embroidery, etc. The effects from consuming it can vary from one person to the next. Sometimes it can be profoundly illuminating, but, unlike peyote, scopolamine as found in kieri, can “produce fever, delirium, convulsions, and collapse. Death may occur in children, the elderly, the debilitated, and any persons unusually sensitive to the antiparasympathetic effects” (Weil 1980: 168). It can provoke a kind of “frenzied madness” and can take people into violent, frightening dreamscapes filled with monsters and evil (Weil & Rosen 1983: 132). In these extreme cases the supplicant may never return to his normal waking state and will wander the countryside in a delirium for the rest of his or her life. Thus, making an alliance with kieri can bring formidable power to the seeker, but it can also draw him or her towards the dark side where shamans practice sorcery as their specialty, summoning evil, even death for their victims. There have been few studies that address kieri and all that surrounds this potent plant; further research will uncover more extensive information on the dark side of Huichol shamanism (Furst & Myerhoff 1966; Knab 1977; Furst 1989; Yasumoto 1996; Fikes 2020).

THE SHAMAN’S POWER OBJECTS

Shamans are equipped with an array of power objects that enable them to communicate with the gods. The shaman apprentice learns about these objects and acquires the necessary materials and fashions them into his or her own personal tools of power. First and foremost is the plumed wand, muwieri, that the shaman holds firmly in his or her hand while singing during ceremonies, when blessing people and offerings, and while performing healing rituals (fig. 10). The stick-like wand is made from brazilwood (Haematoxylum brasiletto), a tree with red-colored wood that, according to myth, carries the heart and the blood of the creator goddess, Takutsi Nakawe. Special feathers are attached to the wand from a range of birds, mostly raptors. Two tail feathers hang down from the wand, and attached to the top are a number of shorty fluffy feathers from under the wing of an eagle. It is said that these represent the soul of the bird and of the muwieri.

Figure 10. Muwierite, feathered wands of power essential for all shamans. Figura 10. Muwierite, varas emplumadas de poder esenciales para todos los chamanes.

Feathers from particular birds are considered to be especially aligned with specific gods and using a muwieri with these feathers facilitates communication with them while singing. Owls are feared by some and sought by others; their feathers are also made into muwierite (plural). The owl is admired because it is said that this bird knows how to dream. Owls are observed to begin singing at dusk and sing throughout the night into the morning. It is believed that shamans who use an owl-feathered muwieri do not tire or get hoarse when they sing in an all-night ceremony. Parrot feathers from the tropical lowlands of the region are prized because they are birds of the fire god Tatewari and help sing to the fire. Indeed, shamans carry a variety of feathered wands for achieving specific objectives. A certain feathered wand is used to catch the soul of the dead in the form of a rock crystal ‘urukame. Another feathered wand is used to kill itauki, which are envoys of evil shamans that appear as small malevolent animals visible only to shamans (Casillas 1996: 221). Certain kinds of healing practices require other feathered wands, the same is true for purifying a person or offerings, for deer hunting, and for blessing the corn fields. Each muwieri is adorned with two colors of yarn that wind down the shaft. The combination of colors represents various things. According to Rafael Pisano, red is for the deer hunt because blood is sought from deer for offerings. Green represents the color of the sierra and trees where deer can be found. Yellow combined with green indicate the yellow face paint and green peyote. Shamans hunt the birds for their feathers and fabricate their muwierite, turning them into personal objects of power that will serve them well (fig. 11).

Figure 11. A kawiteru, wise old shaman, muwieri in hand gathers sacred water to anoint the heads of pilgrims at the sacred body of water known as Tuimaye’u in the San Luis Potosí desert on the way to Wirikuta. Figura 11. Un kawiteru, chamán anciano sabio, con muwieri en sus manos, recolecta agua sagrada para ungir las cabezas de los peregrinos, en el pozo de agua sagrado conocido como Tuimaye’u, en el desierto de San Luis Potosí camino a Wirikuta.

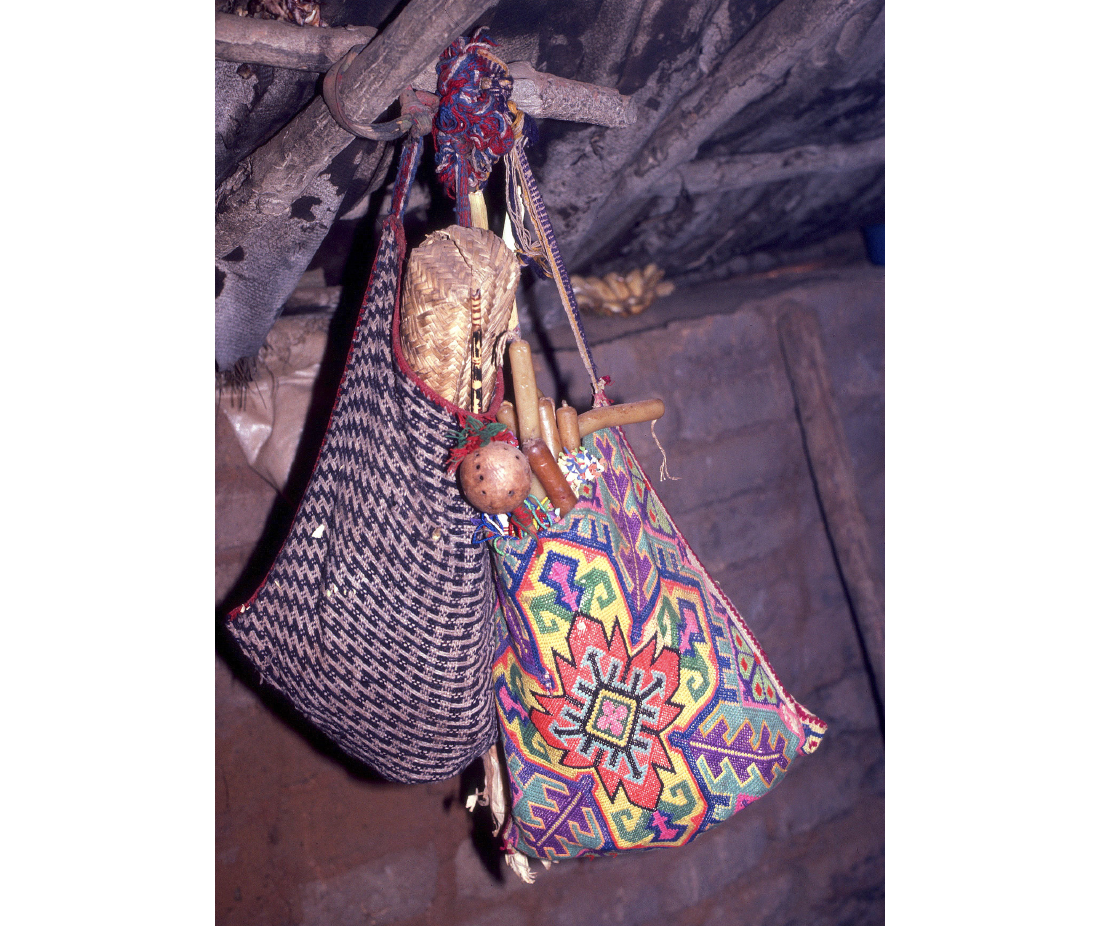

Shamans carry their assortment of feathered wands in a takwatsi, an oblong basket made of woven leaves of sotol (Dasylirion spp.) in specific patterns (fig. 12). María Paulita named the various gods that are represented in the squares on the lid of the weaving. According to myth, these gods were the first to see and touch the first takwatsi in ancient times. Along the sides two rows of braiding represent the road that the pilgrims take to Wirikuta and the return path to the sierra. Accompanying the muwierite in the shaman’s basket are various objects such as small rocks and other materials from nature that were acquired by catching them on shamanic quests as Rafael Pisano described earlier in the text. Shamans also keep a small round mirror in the basket which is taken out and placed on a mat, ‘itari, situated next to the shaman who sits in front of the fire. María Paulita explains that the mirror helps the shaman in ceremonial song follow the sun as it travels through the underworld at night.

Figure 12. Woven and embroidered bags filled with offerings and sacred objects hang from the rafter of the family shrine. Note the takwatsi (woven shaman’s basket) in the woven bag to the left. Beeswax candles and a gourd rattle are visible in the embroidered bag to the right. Figura 12. Bolsas tejidas y bordadas con ofrendas y objetos sagrados cuelgan de las vigas del santuario familiar. Nótese la takwatsi (canasta tejida de chamán) en la bolsa tejida de la izquierda. En la bolsa bordada a la derecha se observan velas de cera de abejas y un sonajero de calabaza.

The ‘itari is also the resting place for the shaman’s muwieri and takwatsi. Currently, shamans may use a burlap or plastic woven bag or a blanket, but in times past, a unique mat was made for this purpose from palm fibers sewn into a rectangular shape. Rafael notes that the fire, the deer, and the mat communicate up to the sun and the cardinal directions. The sun and the gods in these directions respond, and their messages come to the shaman when he sings.

Rafael likens this to a telephone, the muwieri the shaman holds in his hand contacts the gods who are far away; their reply is transmitted to the muwieri and it sounds to the shaman like they are close by. The woven mat listens and records these conversations and shares them with the fire and the sun.

COMPLETING THE SHAMANIC TRAINING

At the end of five years, or however long it takes for the shaman apprentice to be able to heal by extracting foreign objects from a patient’s body, communicate with Kauyumarie, and gain the ability to sing, there is an all-night ceremony to mark the completion of this training. Usually a male calf is sacrificed in front of the fire, and the last set of votive bowls, prayer arrows, and candles are anointed. The next day a meal is shared with all the participants. The initiate is now recognized as a shaman and must leave the last of his or her offerings to the gods. A series of pilgrimages are made to these gods in their sacred places throughout the Huichol territory and beyond to the Pacific Ocean, the peyote desert, and other sacred sites where they dwell. Patients will arrive at the shaman’s ranch to be healed or he/she may go to the patients’ ranches. The shaman can charge for his/her services which can be monetary or take the form of barter. The most challenging cases often require a year-old bull in payment.

Over time, shamans renowned for their healing abilities can acquire considerable wealth in cattle. Their influence often extends beyond the ranch to the larger community where shamans perform more public rituals and ceremonies. As they gain further experience in their profession, they may be selected to serve as the leading shaman in one of the native temples to officiate over the temple ceremonies and pilgrimages in the five-year role of saulixika, who, when he sings, is referred to as Venus or the North Star (fig. 13). Eventually, learned with age and experience, a shaman may reach the level of kawitero, the title applied to the wise, old shamans who through their dreams and consensus, determine who will be the new governing officials in the community every year and decide who will be responsible over a five-year period for carrying out the temple ceremonies and leading pilgrimages.

Figure 13. Eusebio Carrillo, seated in the center, has the role of saulixika, the officiating shaman of the temple, for a five-year period. He holds various muwierite in his hand as he sings. The seated men on either side repeat as if echoing the verses he sings. Figura 13. Eusebio Carrillo, sentado en el centro, cumple el rol de saulixika, el chamán oficiante del templo, por un período de cinco años. Sostiene varios muwierite entre sus manos mientras canta. Los hombres sentados a cada lado repiten los versos de su canción a modo de eco.

SPECIALISTS

Healing one’s nierika (personal designs)

In addition to taking on more leading roles in the community, shamans may advance their skills by specializing in certain realms of knowledge accessible to them in the shamanic world. Again, this is a five-year quest. Shamans may focus on healing individuals through metaphysically repairing and balancing his/her nierika, one’s personal designs. It is believed that everyone is born with special designs located on the cheeks, wrists, throat, and tops of the feet that are seen only by the shaman and the gods. These are the areas where sacrificial blood is anointed or yellow paint is applied during the peyote pilgrimage so that the gods will more clearly recognize him or her. These personal “aura-like” designs are geometric and appear bright and animated with movement when a person is in a healthy state. During illness a person’s designs appear faint, incomplete, and without movement. In healing a patient, the shaman works to restore the patient’s designs to their original state.

Fertility

Some shamans specialize in healing infertile couples desiring to have children; these shamans are known by members of the community to have exceptional powers to select the sex of the child, if the couple requests it, and to metaphysically place the fetus in the woman’s womb. María Paulita Minjares explained that she became a fertility specialist because of a calling she had as a girl on the pilgrimage to Wirikuta (fig. 14). She related this to me through her son who explained that she had eaten peyote on the way to Wirikuta. When the pilgrims stopped at a sacred fresh water lagoon. There,

[…] in the water she saw as if a lot of little children were sprouting from the water. Then someone, one of the pilgrims was giving water to the rest of the pilgrims. She [Maria Paulita] cupped some water in her hand; it looked like she had a small child in her hand, that she had grabbed a very small child. There the shamans told her that this was her luck and her life (María Paulita, personal communication).

Figure 14. María Paulita Minjares is a shaman that specializes in fertility and is the head shaman in her family ranch. Note the votive bowl in her left hand and muwieri in her right. She received her calling when she was younger on the pilgrimage to Wirikuta. Figura 14. María Paulita Minjares es una chamana que se especializa en fertilidad y es la chamana líder en su rancho familiar. Nótese el cuenco votivo en su mano izquierda y el muwieri en su mano derecha. Ella recibió su llamado cuando era joven, durante el peregrinaje a Wirikuta.

Treating scorpion stings

A shaman may specialize in curing people stung by highly poisonous scorpions in the genera Centruroides and Vaejovis. A drop of venom from the tail of one of these scorpions can kill a baby, a child, or an older adult. Healthy adults can suffer a serious episode of anaphylactic shock, made doubly urgent if there is no epinephrine treatment available. Rafael Pisano has specialized in curing scorpion stings by making a special vow with the scorpion god, Paritsika, and by forming alliances with some of the animals associated with this scorpion in order to treat patients who have been stung. Every ranch, led by the shaman in the family, creates a shrine for the scorpion god where they leave offerings and feed the scorpion god with sacrificial blood and ritual food during ceremonies (fig. 15). One shaman, Santos Aguilar, explained that in order to specialize in curing patients stung by this highly toxic predatory arachnid that he ate live scorpions, a total of five; as each one made its way down to his digestive tract, he said he could feel them stinging him inside (Susana Valadez, personal communication).

Figure 15. Votive bowl and offering at the family shrine to appease Paritsika, the scorpion god, and to protect family members from its sometime lethal venomous sting. Figura 15. Cuenco votivo y ofrenda en el santuario familiar para apaciguar a Paritsika, el dios escorpión, y proteger a los miembros de la familia de su picadura venenosa a veces letal.

Wolf shamanism

Another shamanic tradition in Huichol culture which is very ancient and rarely, if ever, practiced in contemporary times is nagualism, becoming a wolf shaman. This requires five years of training in which the shaman leaves offerings to the wolf god Kumukemai at his mountain shrine and communicates with him through his dreams. The plants that help the initiate could be kieri, peyote, or mushrooms that are described as red with white spots.(6) Santos relays (Valadez 1996: 286-287) that at the time the wolves enter the shrine the man loses consciousness. In his vision the wolves take him to their den and “fix him up”. The wolf apprentice will do five somersaults in the sacred directions. If he is fortunate and transforms into a wolf, he is ready at midnight to go hunt deer with his wolf companions. Santos relates (Valadez 1996: 297-298):

[…] while I am in my human form, both the wolves, and other Huichol wolf-shamans, can recognize me as one of them. They recognize me because I now have the wolf sign on my face and wrists, which tells any wolf who I am, and how far I have gone […]. Once a person knows how to turn into a wolf, the wolves will always be at his beck and call.

Guiding the dead

As we have seen, Huichol shamans care for the souls of people as they are born and throughout their lives; they are also charged with assisting the souls of family members at death and beyond. Shamans take a leading role in guiding the souls of the deceased through a ceremony. The shaman sings, and, with the help of Kauyumarie, he or she finds the soul of the deceased as it wanders and brings it to be present so that the participants can reunite one last time and say their farewells. Through his or her song the shaman safely helps the soul of the deceased to the other world where it will remain in the sky above the peyote desert of Wirikuta.

Wise old shamans can specialize in catching the souls in the form of rock crystals, ‘ürükame. Five or more years after a person’s death the shaman may be called upon to bring the soul of the deceased back to the family in this form. Only the most experienced shamans have the power to do this. Another ceremony is performed in which, through the shaman’s song, he or she catches the rock crystal, which may come from within the fire, from the body of a hunted deer or sacrificed cow, from the corn field, or it may be caught in mid-air. This precious rock crystal is wrapped in a layer of cotton and fabric, attached to a votive arrow, and placed in the family shrine located on the ranch.

The living family members care for the souls of the deceased in prayer and take them out to be present during ceremonial occasions where they are offered food and drink and anointed with fresh blood from sacrificial animals. Over time, the shaman may grab five or six ‘ürükame belonging to the deceased family member. In this way, the shaman helps the family find the soul of its deceased member. In caring for it the shaman neutralizes the danger it can have on the living. Eventually, he will take it to the sacred caves Huichols visit to leave offerings. As an ancestor, the crystalized soul resides forever after with the Huichol gods (Furst 1967; Anguiano 1996; Perrin 1996).

CONCLUSION

Huichol shamans are the spiritual doctors, psychologists, diviners, and religious leaders in the family and the community. Currently, Huichol children are required to attend bilingual primary schools; some graduate and go on to the junior high and high school. A smaller number of Huichol youth continue their educations at the university. This means that there may be fewer Huichols from the younger generations learning to become shamans. The consequences could be devastating without leaders who transmit Huichol cultural knowledge and who are also key to balancing traditional and acculturative Western influences.

The relations that Huichol shamans have with Western religious specialists and medical professionals vary widely, and some are more tenuous than others. Catholicism brought by Spanish missionaries in the 17th-18th centuries never made strong inroads into most Huichol communities compared to neighboring tribes such as the Cora and Tepehuano Indians. Priests are not allowed to reside in most Huichol communities in the Sierra but may receive permission to visit and officiate at ceremonies that are related to the Catholic liturgical calendar, especially during Holy Week (Semana Santa). Even then, shamans may also carry out native ceremonies in the church including baptismal rituals for Huichol children, which establish godparent and godchild relationships. They may also make pilgrimages outside of the sierra to specific Catholic churches where they have an affinity for a particular virgin or saint that they have included but kept separate from their aboriginal pantheon of gods. There, shamans leave offerings and collect holy water to take home for the ceremonies they lead. More problematic are the relations between shamans and Huichols who have converted to an evangelical form of christianity, the latter are referred to as aleyluyas. They have been known to confront Huichol shamans and barrage them with their newly-found religious zeal. It is worth noting that if evangelical Huichols encounter difficulties or illness that cannot be remedied by this christian way of life, they may return to seek out shamans in their family for advice and healing (Otis 1998).

The relationship between shamans and most medical professionals they encounter is much more likely to be collegial. Medical doctors who have received training or have interacted with rural Indigenous communities often work collaboratively with shamans in treating Huichol patients. The underlying belief held by many shamans is that Western doctors may be able to cure the body, but only shamans are able to discover the root cause or causes of illness. As such, shamans are able to heal the body and the soul. At the time of this writing, the effect that the covid-19 pandemic may have on Huichol communities where malnourishment, tuberculosis, and other illnesses that weaken the immune system are not uncommon, is extremely disconcerting. Pandemics such as measles and smallpox have struck the Huichol sierra at various times in the past and gravely impacted the population. Huichol shamans in the community of San Andrés Cohamiata ingeniously developed their own technique for immunizing children with smallpox. Evidently, shamans used the thorns of the huitzache plant “[…] to pierce the skin eruptions of people already suffering from smallpox and extract the liquid from them. With the permission of the parents, they would then inoculate the arms of healthy children with this liquid […]” (Casillas 1996: 219). Huichols from this community credit the disappearance of smallpox to a prominent shaman named Carrillo who has since died. Their oral tradition tells that

to “cover up” –that is, calm– the disease he made a pilgrimage to Haixáripá, a sacred place on the slopes of Popocatépetl, the great snow-covered dormant volcano near Mexico City, where Huichol mythology says smallpox made its first appearance. His efforts were successful and smallpox never again bothered the people of San Andrés (Casillas 1996: 219).

Only time will reveal how Huichol shamans will treat people affected by the covid virus or any other pandemic that may arrive to their community. One thing that is certain is that shamans will work along with Western medical professionals to care for the sick and look over their souls; and if death falls upon a patient, the shaman will also be the one to look after his/her well-being in the afterworld.

Despite the onslaught of challenges brought by the Western world to Huichol culture, their shamans, with the guidance of the deer god, Kauyumarie, have been and continue to be paramount leaders who help to navigate through an intensely changing world. Huichol shamans, working alongside their Western-educated countrymen and women, will chart the future of their people and destiny of the Huichol people.

Anguiano, M. 1996. Müüqui Cuevixa: “Time to Bid the Dead Farewell.” In People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion and Survival, S. Schaefer & P. Furst, eds., pp. 377-388. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Beck, D. 2005. Biology of Gila Monsters and Beaded Lizards. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Casillas, A. 1996. The Shaman Who Defeated Etsá (Smallpox): Traditional Huichol Medicine in the Twentieth Century. In People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion and Survival, S. Schaefer & P. Furst, eds. pp. 208-231. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Fikes, J. 2020. Beyond Peyote: Kieri and the Huichol Deer Shaman. Berkeley: Regent Press.

Finson, B. 1988 (Ed.). The Huichols: A Nation of Shamans. Oakland ca: B. I. Finson.